|

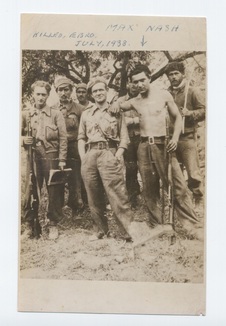

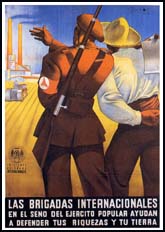

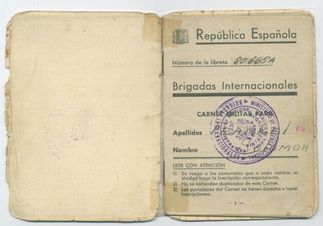

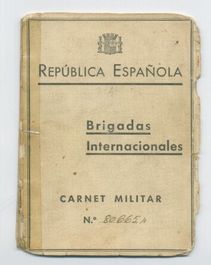

On the anniversary of the creation of the International Brigades in Spain, the GazpachOmnk presents a very special interview with British International Brigadista: Sol Frankel.  Sol Frankel Sol Frankel One warm and sunny October evening, many moons ago I received an unexpected phone call. "Could I give a talk on Living in Spain at a sea-front Hotel in Almuñecar, on the Granada coast?" The presenter had fallen ill and they needed a quick replacement. That same evening I stood in front of a group of British pensioners attempting unsuccessfully to satisfy probing questions on oily food, the availability of fresh milk and why more Spaniards don't speak English. At one point I managed to lever the subject away from British culinary needs and onto Spanish Culture and Spanish history. Immediately, someone began to snore, several couples shuffled out towards the bar, whilst the rest passed round a packet of Fisherman's Friends. One man, however, sitting at the front, looked up and waved his walking stick in my direction as I started to talk about the British volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. "Yes?" I said. He signalled for me to approach . "I remember," he said, thrusting the stick at me as though it was a rifle, "the only weapons we had then were antiquated Russian rifles that had come via Mexico." "You remember?" I said. "Yes, of course." He replied. "Why wouldn't I? After all, I was there." An Interview With Sol FrankelSol is a small man of medium build, wearing a faint grey moustache, fragile glasses and a warming smile. He leans on a worn walking stick. His right arm hangs redundant at his side. I found him sitting alone at a table in the cafeteria the following day. He looked a little unsure as to whether I would come for the arranged interview, but when he sees me his face breaks into a welcoming smile. I go to shake his hand, but it is too late. I forgot about his damaged arm. But Sol, even at 88 years of age, is quicker than I. His left arm shoots across and clumsily grasps my right. His eyes smile, and I relax. I pull up a chair alongside Sol who is clutching an A4 envelope to his chest. "Not many people ask about this part of my life any more," he says. "Especially younger people."  Sol with pipe at the front Sol with pipe at the front I had left my dog tied-up outside the hotel. So I asked if he wouldn’t mind moving out to the terrace, so as not to leave the animal alone. Whilst we sit down outside, he immediately springs back up. "I'll go get us a tea," he offers. Before I can respond he has disappeared back through the Hotel lobby doors. Whilst he is inside, I glance at the documents he has left on the table. An International Brigade membership card is dated 1937. It is a little faded by the sun, and crumbles at the edges of the pages. It carries no photo, but plenty of official Republican stamps on its delicate surface. This is the first time I have ever seen an official document from that period. The first time I have ever held in my hand an authentic document from the fateful Spanish Second Republic. I felt it ought to be in a museum, but glad it wasn’t. Underneath the card is a group photo of soldiers at the front. One man, with a characteristic moustache is smoking a pipe between several other men. He wears a hat titled in a rebellious fashion and looks familiar. Another man is bare-chested. Above him is an arrow that someone has drawn and the word “killed” scribbled above. East London To SpainBorn 31st March 1914 in Stepney, East London, Sol describes himself as a typical anti-fascist, so prevalent then amongst the Jewish working classes living in the midst of the inner city. I begin by asking him about what motivated him in going to Spain to fight for a people he knew nothing of.  "I was a member of the anti-fascists," he explains, telling me that he had volunteered to work for 5 weeks in a camp for 3000 refugee children from Bilbao. He recalls the time as formative, digging latrines and teaching English to the adults that had accompanied the children. It was after this, as the civil war continued that Sol approached the British Communist Party to volunteer for the International Brigades. They lent him the fare to get himself to Paris by boat. France and England had signed a policy of non-intervention in the Civil War (though both countries were continuing to sell arms to the fascist states as well as conduct business with Franco´s Nationalists). Officially though, neither country could be seen to help the Republican cause and so, when asked on the boat over to France about his destination, Sol had to pretend he was visiting an uncle in Paris. He recalls that once there, he was met by the French Communist Party who provided him with a ticket to the Pyrenees. On the train towards Spain he was told to keep his head down as French Police would be looking for foreigners making their way to the border. "But they weren’t all bad", he adds smiling. "I remember some French Police giving us the Communist salute as we peered out the windows when the train departed from some of the stations." At the border he was taken to a series of safe houses whilst gradually, more volunteers joined him from other countries. “There were three or four of us from Britain” but many others from France, Italy and even Germany. Eventually a coach arrived one night and about 70 of us went into the mountains." From where the coach left them, they had to walk in a single file for 7 – 8 hours across the Pyrenees until they entered Spain. Sol remembers that they were issued deck shoes for better grip and to make less noise, meanwhile his boots were tied together by shoe laces and hung around his head. He also remembered after the long walk through the night, his first glimpse of the Mediterranean at sunrise. The distinct blue of the sea was a sight he still remembers vividly. Finally, another vehicle took them to Figueras where they were all housed in the town castle for a few days before being moved on. Finally, he was later moved to Gerona and then Albecete where he undertook his training. “Most of us had done some military training” he recounts, “so were already familiar with a lot of it. We worked in companies according to where you were from. The training lasted two weeks before being moved to the front. For some reason I stayed for four weeks. I was lucky I suppose” Running at the Front Italalian tanks Italalian tanks Sol was a sergeant with 18 men under him. One of which he remembers was Lewis Clive who went on to become the company commander. After his 4 weeks training, Sol was moved to the front as part of a company of 650 men. He remembers the day clearly. He rests both hands on his stick and leans forward: "That first day on the front was one I will never forget." It was his 24th birthday and the group had walked straight into a large Fascist tank division. “The tanks were Italian and as close to me as that tree is over there,” he points his rifle-stick at a palm tree no more than ten yards away. "Out of the 650 men only 90 made it back to the camp." Sol picks up his tea, pauses, his cup suspended above the table, his eyes searching for some meaning in the events of that day. "What happened?" I ask. "They were all captured or killed." "How did you manage to get away?" The cup remains suspended in the air. Slightly shaking, he lifts the tea cup to his mouth and takes a sip. He looks back to me. " I ran." He said and his endearing smile returns. "I could run really fast in those days”. Wounded After that, he was given the job to hold a mountain pass near the mouth of the Ebro. The most vivid memory of this time was when the bridge was blown up and they couldn’t get the equipment across. "Who couldn't Sol?" He looks up. His eyes are unclear. "Some people", he says. His details are vague. He is trying to recount a story from 65 years ago. Certain events are clear, others have left him a long time ago, inhabiting other places now. I tap on the photo lying on the table. "That you?". "Yes", he replies. “ He points at the rifle in the picture. "We used Russian arms that had come via Mexico. A lot were not very good and there was a shortage of ammo.”  Issue by the short lived Spanish Republic Issue by the short lived Spanish Republic “And how did you receive your injury Sol?” I finally ask. Sol lifts his stick-rifle and takes aim at two pensioners shuffling up the steps from the beach. “I was shooting facing this direction” he recounts, propping his bad arm onto the table. “When suddenly I felt a pain in this arm. I had been shot through my right arm from the back.” He puts down his weapon and rolls up his sleeve to show a scar on either side of his upper arm. “Bullet went right through see? It felt like I had been kicked by a horse. A couple of mates held me up and helped me to where a stretcher could get to me. Eventually an ambulance came and took me to the infamous cave hospital. From there I was eventually moved to a Hospital in Barcelona. I stayed there 3 days. I remember we were bombed every night in that hospital. I thought I would be out in a couple of days and back to the front. But the bullet had severed the muscle and the nerves. So I was moved to the International Brigade hospital. From there I was eventually returned home." "And what was it like to get home?" Sol smiles. "We received a truly warm welcome on return at Victoria Station. Hundreds, if not thousands came out to greet us. By that time, of course the International Brigades had been disbanded as you know.” (In a futile attempt to persuade Franco to stop accepting Italian and German assistance, the International Brigades were disbanded and sent back to their respective countries. Many, such as the German and Italians volunteers had no country to return to. It was a controversial decision. Meanwhile, Franco continued to receive International support.) International Brigades and Spanish Recognition Sol digs into his envelope he has been carrying with him and produces a yearly bulletin from the members of the International Brigades. “Did you see the memorial sculpture on the south bank?” he asks handing me a leaflet. "Yes, Ive seen it Sol". “And did you see this?” Sol produces from his back pocket a life membership card for the UGT (UNION GENERAL DE TRABAJADORES), and from the envelope again a letter from the Spanish Government offering him Spanish Nationality in thanks for his sacrifices made. “I didn’t take them up on that because it would have meant giving up my British Nationality."* "It stops many of us taking up Spanish Nationality Sol." "Silly really. Isn't it? Otherwise, I would have.” “Do you always carry this stuff around with you Sol, when you come to Spain that is?”: “When I come to Spain yes. Although, not many people ask me, or are interested these days. Do you know I was interviewed for the David Leech film,? I was interviewed by students of Paul Preston." "No, but I'll make a point of seeing it Sol". "Yes," he says. "You should see it." His arm goes limp again. His eyes look out to sea as though he were searching for something. "No, not many people ask me now. You see there is not many of us Brigadistas left. Probably just about 20 now." He rests both hands on the top of his walking stick again and looks over to me. His eyes flicker and he says: "You know, each year we still get together." Then his smile fades a little as his chin drops onto his hands. "But each year there are less and less of us. Once upon a time we would have a meal and spend a few hours together. Now we just meet for a drink and don’t stay long. We are all getting on a bit now you see.” 4 FINAL NOTES 1. This Interview between Sol Frankel and the gazpachomOnk took place on Saturday 26th October 2002, Hotel Helios, Almuñecar, Granada. 2. Sol Frankel died on 18th May 2007, aged 93. 3.* It would not be until the controversial 'Ley de Memoria Historica' that it would be legal for International Brigade Volunteers to hold both Spanish and country of origin nationality. 4. For more stories on volunteers in the Spanish Civil War see the Spanish Book library here

robert webb

14/9/2014 01:40:30 pm

To this day franco has left a fearful legacy. The truthful accounts of this time must prevail 12/10/2014 12:06:31 pm

'The truthful accounts of this time must prevail' - from both sides... Comments are closed.

|

StoreBooks

Videos Audio |

PDFs to Download |

|